Co-op and condo board members usually are volunteers who live in the building and contribute their time and expertise to help their community. Ideally, they ensure that the building runs well and efficiently, and that residents’ investments in their homes are protected. It takes a bit of know-how to accomplish these seemingly routine goals, though, and new board members sometimes don’t have that knowledge.

While some new board members enter their volunteer positions with professional experience that makes them familiar with how buildings are run, many have no related experience. Complicating matters is the fact that new board members often start their volunteer positions without understanding the full scope of the responsibilities they've just accepted. Issues such as how to handle confidentiality among residents or in employee-related matters, the fiduciary responsibility of board members, and other building-related matters may not be clearly understood by a new board member. Unfortunately, that ignorance can lead to some troublesome missteps.

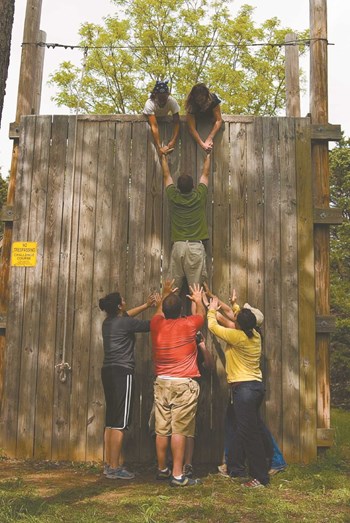

Current and former board members as well as managers can help to smooth the transitions of new board members into their new leadership roles. By informing new members of their actual responsibilities, which are covered in the building’s governing documents, and by focusing on the board-related tasks at hand, veteran and experienced board members can help newbies orient themselves in ways that are helpful to the entire community.

Ignorance Hampers

New board members who do not understand their full responsibilities as board members—or who don’t comprehend the limits of those duties—can be the source of friction and headaches on co-op and condo boards. Misconceptions run the gamut from the board member expecting he’ll have to do too much, to a board member assuming he’ll have to do very little, to the wrongful assumption that board members are paid. Because of these erroneous perceptions, it’s good for prospective board members to attend meetings and familiarize themselves with the process prior to running for a seat on the board.

Only some would-be board members follow such a course. Some think the job is an incredible amount of work, while others think the job is no work at all, says Jim Stoller, president of The Building Group in Chicago. “Some [aspiring board members] run for a seat on the board because they want to make connections, or some do it as popularity contest, while others want to help the community. There can be a problem when some people run for the board because they want to sell their condo,” Stoller says.

Contrary to popular perception, being a board member of a co-op or condo board doesn’t have to be time-consuming. These residential boards are not corporate boards, and they are aided by professionals who consult them. Those consultants should be allowed to do their jobs, and their advice should be sought for matters in their areas of expertise. Legal matters obviously should be deferred to the attorney, construction matters to the engineer, and building management problems should be the province of the building management company. These people are experts in their respective fields and have years of experience and accumulated knowledge that a wise board will tap.

“If a board member manages his time well and works with the property manager, he shouldn’t have to do as much work as he might think he’ll need to,” says Scott Seger, president of Forth Group, a residential and commercial management company in Chicago. Some boards incorrectly view themselves as acting similarly as corporate boards, which can result in problems, he says.

Another common misconception of some new board members is that they will be running the day-to-day operations of the building. This false perception keeps some prospective board members from campaigning for the job, says Michael E. Rutkowski, principal/owner of First Properties, LLC in Chicago. “Usually there’s a management company running the building. The board’s role is to make the major decisions regarding the community,” he says.

In their new roles as elected community leaders, board members must remember they are representatives of the community. Board members must be fair, and they must put the desires of all the community’s residents ahead of their own individual desires. Not all new board members understand this, even after they are sworn in.

“Some people think their personal agendas will be satisfied when they become new board members,” says Thomas A. Skweres, president of Wolin-Levin, Inc., a residential property management company headquartered in Chicago. “Other new board members don’t realize that being on a board is as much work as it is. But they are running a business.”

Board members who are new to the job should have at least a summary of Robert’s Rules of Order to understand how meetings are run. Forth Group gives new board members a one-page treatment outlining the duties of the job. It’s a good idea for the property management firm to meet with the board members at the start of their elected terms, to debrief the board on the property’s finances, ongoing projects, and other matters.

Because the first chore of any new board member is understanding his or her role, he or she should begin by reading all of the building’s governing documents. New members also should read and understand the building’s bylaws, the Illinois Condominium Property Act (ICPA), and any other applicable rules and regulations. And a new member should read the building’s meeting minutes for at least one year prior to his or her arrival on the board. This is not as time-consuming as might seem. Most meeting minutes are just a page or two long, and with about six meetings per year, that’s not a lot of reading.

New and experienced board members should take advantage of the available information on running a building. Such info can be found through organizations including the national and Illinois chapter of the Community Associations Institute (CAI) and the Chicago-based Association of Condominium, Townhouse and Homeowners Associations (ACTHA).

“They don’t have to reinvent the wheel. A lot of the basic stuff has been established,” Rutkowski says. “Taking advantage of these resources will make board members’ jobs a lot easier.”

Wolin-Levin, Inc. helps new board members get acquainted with governing documents, and also gives them an overview of how managing the building works. The firm brings in the company accountants and information technology staff to speak with board members about how the building’s business is conducted. It also advises the community’s elected leaders to think about the big picture.

“I tell board members they should be thinking long-term—three years, four years, five years and even ten years in the future,” Skweres says.

Since a long-term vision is essential to sound building management, boards tend to have staggered terms for board members, meaning all members are never up for election at the same time. This allows the board to convey an institutional memory, where more experienced board members can relate the experiences of having dealt with the same or similar problems before. Some of this knowledge can be gained by a new board member doing their own homework. A board member who has read the meeting minutes and is aware of a problem such as a recurring roof leak, for example, might be able to remind the board that the last roof work done had a warranty.

New members who want to be fully informed must review the building’s capital reserve study, and talk with the property manager about any ongoing projects, if the manager has not already scheduled such a meeting.

Passing on the institutional memory of a building shouldn’t be confined to property managers and consulting professionals. Former board members can be helpful to newer board members for years after their service on the board has ended. Having a transition meeting between former and current board members and new board members makes the orientation process less daunting for the newbies. “Former board members should make themselves available to new board members,” Rutkowski says.

Having complete sets of building records is important, too. New board members who want to do their best will be reading meeting minutes and other building documents, and if those records are incomplete, the board member will get just part of the story. They might form the wrong idea about an issue or make a simple mistake because of it.

The Building Group and some other companies offer specialized training to boards of co-ops and condos. The Building Group offers an introductory one- to two-hour training class for new board members. The firm also offers a monthly seminar that educates board members in the nuances of running a co-op or condo.

In addition to knowing the details of years of past meeting minutes and being familiar with the building’s reserve study (which should be revised every five years), new board members should have a list of the community’s capital improvement projects during the past decade, Rutkowski says. Board member manuals provided by the building also can be very helpful, but most buildings don’t provide such a guidebook.

Wolin-Levin offers quarterly meetings for new board members and their more experienced peers. One of the things addressed at these informational get-togethers is smart time management—board members should not have meetings that drag on and get little accomplished. To avoid such wasteful meetings, a board must do its homework before meetings. And the board must be equipped to do that homework, by having a process through which board documents such as management reports are sent to board members prior to a meeting. These documents should be sent at least a few days before the meeting so the board has time to read and comprehend the documents. That way, precious board time is not being spent in getting the board members up to speed with the issues they will be dealing with in the meeting.

There is a limit to the patience of board members and residents who attend board meetings. No one wants to stay all night at a meeting, yet some boards seem to be unable to speed up the process. When things seem to be getting too bogged down during meetings and not enough is being done, it can kill the spirit of volunteerism that brought board members together in the first place. Boards with this problem should, again, listen to their professionals.

“We talk to boards about not having meetings that last more than two hours,” Skweres says.

One way to accomplish this goal of avoiding marathon-length meetings is to have a “workshop” meeting, which can be a closed-door meeting prior to the regular voting meeting. At such a meeting board members can get up-to-snuff on issues they’ll be dealing with, and perhaps ask questions they wouldn’t feel comfortable asking in a regular, open public meeting.

Remember serving on your association board is not only a worthwhile endeavor but gives you an opportunity to influence the governance of your most important asset—your home.

Jonathan Barnes is a Pittsburgh freelance writer who frequently contributes to The Chicagoland Cooperator and other publications.

Leave a Comment