Every co-op, condominium, and homeowners association has rules and regulations that residents and their guests must abide by. For the most part, they’re usually pretty straightforward and have minimal impact: no 200-pound dogs, no smoking in the mailroom, no bowling in the hallways.

Sometimes, however, a board will try to implement a rule that oversteps its bounds, is unenforceable, or just rubs residents the wrong way. Take Chicago condo owner Pam D., for example. She and her husband are owners of a large loft on the fifth floor of a condo building in Chicago’s hip Printer’s Row neighborhood. They have lived there happily for over four years, and never taken much issue with the various rules and regulations dictated by the condo’s board. Until now.

“I bike to work at least three times a week and have done so for years,” says Pam. “And out of nowhere, we get a notice that says the bike rack in the basement is now first-come, first-served.”

This wouldn’t normally be an issue, but after the interior hallways got a fresh paint job and new carpet, the condo board had concerns about handlebars bumping and chipping paint, and muddy wheels leaving tracks—so the bike storage notice also dictated that residents were no longer allowed to bring bikes into their apartments. The basement bike rack is packed—there isn’t an inch free—leaving no place for Pam to park her bike.

So what makes a good rule, and how can condo and co-op boards know the rules they're making and enforcing are fair, just, and legal? The answer is part protocol, part common sense.

What's in a Rule?

Attorney Allan Goldberg of the law firm of Arnstein & Lehr, LLP in Chicago first explains the difference between the bylaws and house rules in a co-op or condo building, an important distinction when discussing board power.

“Bylaws for each type of community association deal with the same matters,” says Goldberg. “[They] deal with the powers and duties of the association or cooperative corporation; they establish the day-to-day governance of the association…for example, the bylaws establish the number of directors, the terms of the directors, matters germane to elections, the officers' specific duties, the manner of resignation or the removal of directors, the process of adopting annual budgets, the process of adopting rules, and the general powers and duties of the members of the board of directors.

“On the other hand,” Goldberg continues, “rules and regulations are adopted by the board of directors and deal with specific rights, privileges, and restrictions on the condominium unit owners, shareholder-tenants of a residential cooperative, and homeowners in a townhome or single-family home subdivision. They deal with the operation and the use of the property.”

While residents are occasionally the breakers of rules, they are never the makers, as the creation of rules is within the sole province of the board of directors, and residents don’t have the power to directly amend them. Under the Illinois Condominium Property Act, it is the board—not the residents—that votes to adopt, amend or revise the rules.

Patrick T. Costello, who is with Keay & Costello PC, Attorneys at Law, in Wheaton, further explains, “Boards, or sometimes a committee, usually starts the drafting process of the first set of rules. Often a board will use a similar community's set of rules as a starting point. Once the board has created a set of rules, they should circulate the rules to the members…while the Illinois Condominium Property Act does not require member participation prior to adopting the rules, it is a good practice to allow the members to voice concerns and comments regarding the rules prior to the board adopting them.”

And getting feedback or buy-in from residents goes a long way toward cultivating harmony among neighbors, say the pros. While the bike rack rule in Pam D.'s building might not seem that extreme or brought down on high from an evil condo board, it certainly has miffed Pam. “I’m either sneaking my bike in through the back stairwell, hoping a neighbor doesn’t see me and report it or confront me,” she says, “or I’m locking it up on the street, worried all night I’ll come out the next day to see that my seat, wheels and handlebars have been stolen. It’s not ideal.”

Enforcement and Fairness

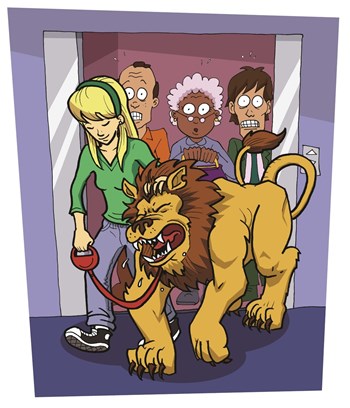

Pam D.’s building has a few other rules and regulations, including quiet hours on the shared rooftop and a rule that residents with dogs in tow ask permission before stepping on to an elevator with other passengers. These rules, specifically the dog/elevator rule, aren’t strictly enforced. “I rode the elevator with five dogs at once last week,” laughs Pam. “No permission requested!”

When it comes to wrist-slapping and penalty enforcement, typically the same principles apply regardless of co-op, condo or homeowner’s association, and Goldberg notes there are many variations on the penalty theme. Rule breaking residents can expect anything from a warning or a monetary fine, escalating to violation hearings and/or imposition of sanctions if the behavior isn’t curbed.

Goldberg explains, “If reasonable and uniformly applied, rules can do just about anything if the residents are treated fairly and the rules are oriented toward stopping a behavior or an action which isn't in the best interests of the community association.”

Costello suggests getting a lawyer involved, “when the fines and violation notices are not solving the problem or obtaining compliance from the offending owner. Then it's time to get legal counsel involved.”

Goldberg concurs, stating it’s time for legal counsel to be consulted, “when it becomes clear the board of directors, a committee appointed by the board, or the property manager are unable to get the resident to stop the offensive behavior or rules infractions.”

But what if the “offending owner” is up against an unusual or overly strict rule? Beyond bikes and bowling bans, what rules go above and beyond a “good” rule, a rule Costello describes as “designed to further the overall welfare of the community and to make the building or community a nicer place to live?”

Goldberg explains that until a change to the Illinois Condominium Property Act three years ago, “Some associations adopted rules banning the placement of anything outside the front door of the condominium units in order to maintain a uniform appearance. This type of rule prohibited placing religious objects or even holiday displays outside the door of the units and, if strictly enforced, made homeowners protest that such strict rules imposed unconstitutional and discriminatory sanctions on them in violation of fair housing laws.”

As a response to these situations, the act reads: " ... No rule or regulation may impair any rights guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States or Section 4 of Article I of the Illinois Constitution including, but not limited to, the free exercise of religion, nor may any rules or regulations conflict with the provisions of this Act or the condominium instruments. No rule or regulation shall prohibit any reasonable accommodation for religious practices, including the attachment of religiously mandated objects to the front-door area of a condominium unit. ”

Goldberg goes on to say that a good rule “treats all owners or shareholder-tenants the same, is adopted with a view to a uniform, non-discriminatory, arbitrary, or capricious application. The rule is ‘reasonable’ and fair, adopted to address certain situations in a non-discriminatory fashion.”

On the flip side, “bad” rules are, as Goldberg describes, “not adopted in the best interests of the entire community association. They favor one group of owners over others, and are generally not created in the spirit of imposing reasonable restrictions on the residents' rights. Rules imposing large fines for small offenses are considered punitive. ‘Let the punishment fit the crime’ as they say.”

Costello adds that, “Rules differ from community to community, and generally should reflect what each community values. When a rule is enacted to punish a certain owner or attempt to stop a singular incident, the rule generally does not work. Rules enacted because a board dislikes a certain owner generally creates more problems than they solve. Rules which are applied or enacted discriminatorily could subject an association to legal action.”

If Pam D. and her husband decide to leave Printer’s Row and sublet their loft to move to a more bike-friendly building, their subtenant would be subject to the building rules and regulations (assuming that subleasing is allowed by the board, of course). Costello explains, “Tenants are generally subject to the same rules of the owners and may be subject to greater restrictions. Typically, the additional restrictions relate to the leasing situation itself…If a tenant fails to comply with an association's declaration, bylaws or rules and regulations, the association can send the tenant (with a copy to the owner) a certified letter informing the tenant that he/she has 10 days to remove himself/herself from the premises. Failure to do so can result in the institution of forcible entry to remove the tenant from the property.”

Pam D. does admit that the newly painted walls and carpeted hallways are a great improvement to the building, and that she understands where the board is coming from, “I guess it’s a give and take,” she says. For now though, her next move is to put in a request for another bike rack in the basement and purchasing a sturdier bike lock for when she leaves her bike outside. “Come winter, the bike is going into storage anyway,” she says.

Rebecca Fons is a freelance writer and a Chicago resident.

4 Comments

Leave a Comment